The global drug trafficking continues to grow despite the efforts to combat it. According to the World Drug Report 2023, illicit drug markets continue to expand. The supply of cocaine is growing, social media is making it easier to sell, and synthetic drugs – cheap and easy to produce – are spreading around the world. The harm caused by the “drug economy” is exacerbating many threats: from instability and violence to environmental destruction.

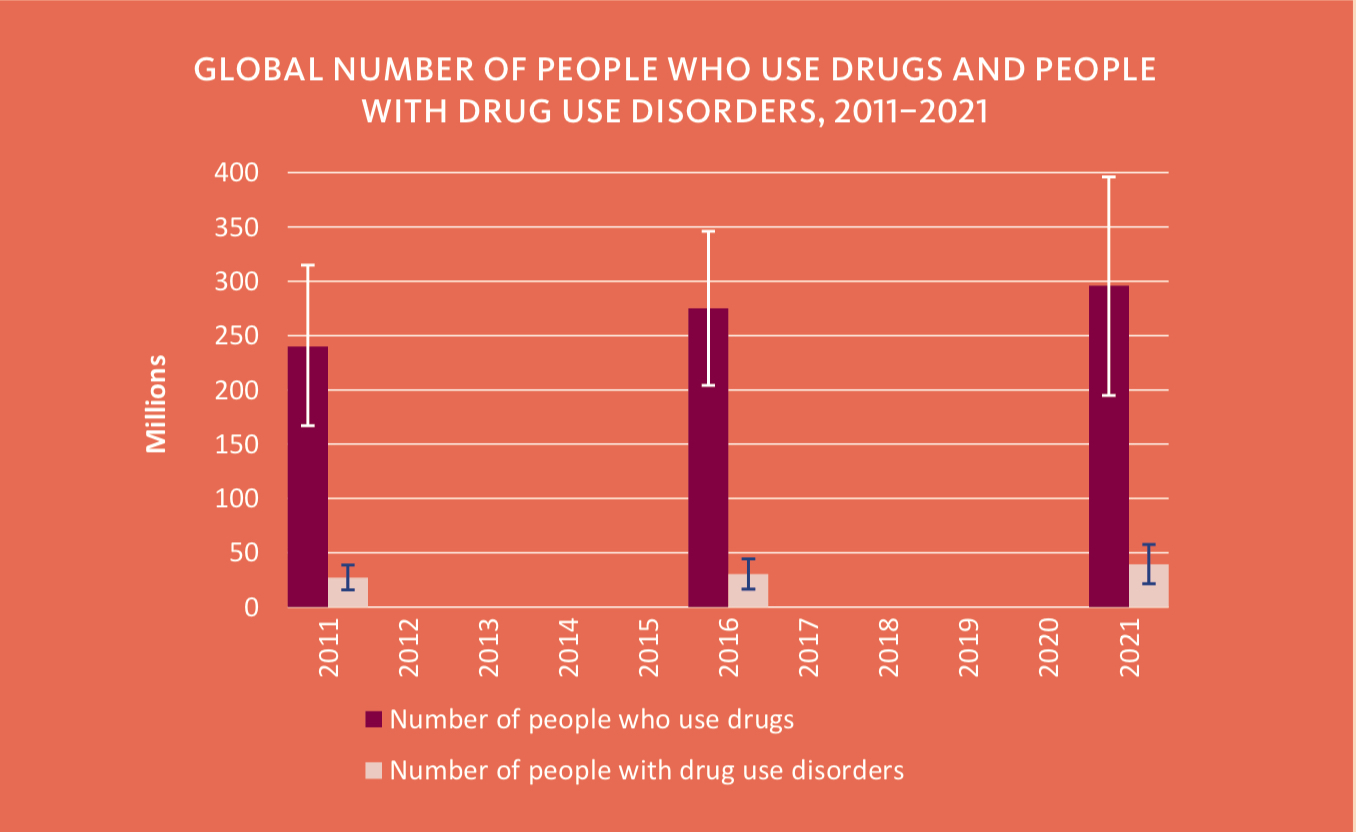

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the estimate of people who use drugs has increased from 240 million in 2011 to 296 million in 2021, i.e. 5.8% of the world’s population aged 15 to 64 – one in 17 – has used drugs in the past 12 months.

Cannabis remains the most widely used drug on the planet. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 219 million people (4.3% of the world’s adult population) used it in 2021. Amphetamines were used by 36 million people, cocaine by 22 million, and ecstasy-type substances by 20 million. About 60 million people used non-medical opioids, 31.5 million of whom used opiates (mainly heroin). The latter continue to be the group of substances that cause the most serious harm to users, including fatal overdoses.

One in 17 people worldwide used drugs in 2021, i.e. 23% more than ten years ago

According to a new report by the Harm Reduction International (HRI), which has studied data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), more than $974 million was spent on “drug control” projects in a ten-year period from 2012 to 2021.

This amount includes the costs of dozens of donors from around the world, led by the US, EU, Japan, and the UK. For example, the US and EU spent $550 million and $282 million from their budgets, respectively, and the UK spent $22 million.

Tens of millions of dollars of this total amount (at least $70 million over the period under study) were allocated and spent in countries where the death penalty is imposed for drug-related crimes. For some experts, this raises “serious concerns about whether such donor budgetary assistance could support regimes that execute people.”

The aid was also used, for example, to train police and special forces in Vietnam and Honduras, which are accused of arbitrary arrests and killings, while another chunk of the funds was used to support surveillance capabilities in Colombia, Mozambique, and the Dominican Republic, and covert police work in Peru.

Paradoxically, the enormous funds allocated to the war on drugs have not solved the problem, but have created a number of new ones, including numerous human rights violations and outbreaks of unjustified violence.

The war on drugs

The so-called War on Drugs began in June 1971, when U.S. President Richard Nixon declared drug addiction “public enemy number one” and increased funding for drug control agencies and drug treatment programs.

Punitive methods: increased penalties, enforcement, and incarceration – served as the basis for the policy of the United States’ expanded efforts to combat illegal drug use.

This coercion-based approach was later implemented in the international legal framework when the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was amended. Since then, for almost 50 years, these approaches have remained virtually unchanged.

Graphics: United Nations Office on drugs and crime_Vienna World Drug Report 2023, Source: www.unodc.org

In 2011, the Count the Costs initiative reported that the fight against drug use, supply and production costs at least $100 billion a year. At the same time, 300 million people on the planet continue to use drugs, and the global market reaches $330 billion a year.

It has become clear that the approach aimed at creating a “drug-free world” has failed. Moreover, along with the enormous costs that have been well documented, serious “side effects” of current policies have come to light.

Punitive methods and prohibition are not working

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has recognized that the current system of global drug control has a number of negative “unintended consequences”. In particular, it referred to “the creation of a huge criminal market, the shift of production and transit to new territories, the transfer of resources from the health care system to law enforcement, the replacement of the traditional drug consumption with new drugs, and the stigmatization and marginalization of people who use drugs.”

After a recent Latin American and Caribbean Conference on Drugs in the Colombian city of Cali, nineteen participating countries issued a joint statement: the traditional global war on drugs has failed and must be rethought, with efforts instead being focused on “life, peace and development” within the region.

“The 50 years of a failed war on drugs had resulted in immeasurable bloodshed and pain in Latin America,” increasing “the vulnerability of our territories and societies,” said Colombian President Gustavo Petro.

He even compared the war on drugs to “genocide,” calling for the recognition of drug use as a public health problem instead of trying to counter it with militarized tools.

According to security sources and analysts, Colombia and Mexico, like other Latin American countries, face ongoing violence caused by the drug trade and the presence of cartels with growing firepower and economic power.

Aggressive drug policies often hurt vulnerable communities more than those who profit most from the business.

The war on drugs has had a particularly negative impact on poor, marginalized and racialized communities around the world, according to a report by Harm Reduction International (HRI).

Mass incarceration and overcrowded prisons, death sentences, deaths of civilians during special operations by anti-drug units, destruction of the livelihoods of poor farmers through the spraying of chemical solutions and the use of other tools of “forced eradication” of crops, violation of the rights of participants in compulsory treatment programs, discrimination and obstacles to health care, – this is just a part of the consequences of the global war on drugs, HRI analysts write.

Among other things, international aid has also gone to support covert police, “intelligence-led profiling,” and efforts to increase arrests and prosecutions for drug-related crimes.

“When you are thinking about development, you don’t really think about using additional funds for these kinds of activities. You think about poverty reduction, working towards development goals in health or education,” said Katherine Cook, head of sustainable finance at HRI, which monitors the impact of drug policy. “This money is actually being used to support punitive measures, like police, prisons, essentially funding the ‘war on drugs,’ even though we know that it is war and punitive policies that have repeatedly failed.”

This year, UN Human Rights Chief Volker Türk called for an end to the “war on drugs,” saying it has failed to stop production while causing mass arrests and killings by authorities.

***

The analysts believe that these vicious cycles can be broken by reorienting approaches to financing punitive methods to support harm minimization policies.

“Punitive approaches have limited results in any field, and the idea that criminal law or prison can produce results beyond them is a common mistake in our modern societies,” Colombian officials said, adding that punitivism must be put to an end.

Prosecution efforts should focus on the main leaders of the drug trade, not on peasants. Demand for illicit drugs can be reduced by educating the population and addressing inequality, poverty, lack of opportunity and violence.

Ultimately, the benefits of such alternative approaches to drug policy are well documented and are guaranteed to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals, including peacebuilding, global health and poverty reduction. In contrast, there is no evidence that punitive and prohibitionist approaches actually curb drug use.

Source: The Gaze