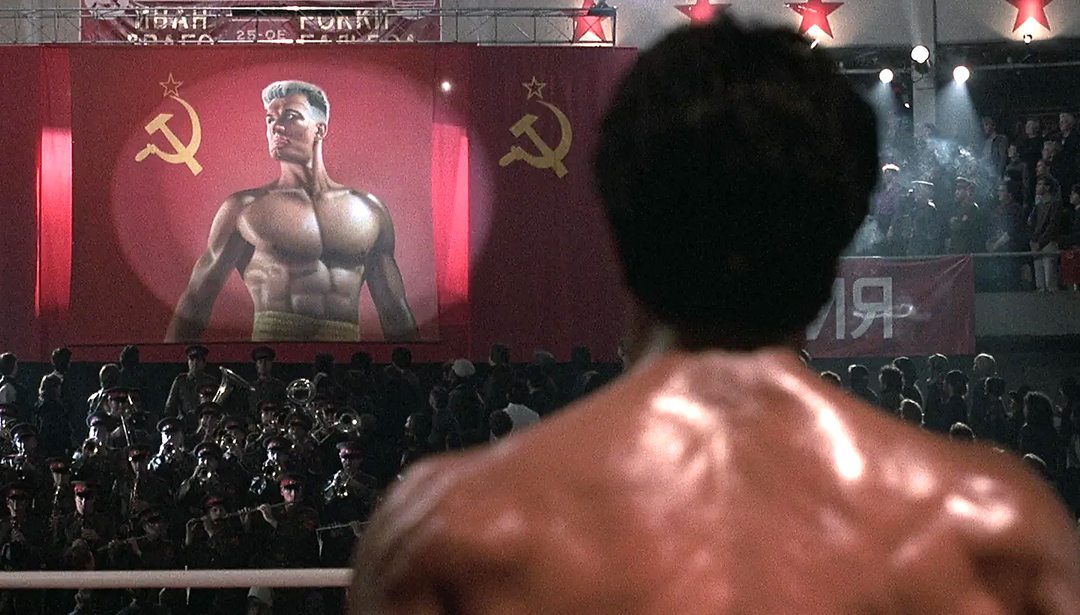

Rosa Klebb and Max Zorin from James Bond films, boxer Ivan Drago from “Rocky IV,” Moscow gangster Viktor Rostavili from “Red Heat,” and even the comedic astronaut Lev Andropov from “Armageddon” – these characters once elicited sceptical smiles. Today, after unsuccessful attempts to “civilise” Russians through integration into the global economy and following a series of wars, both hybrid and full-scale, launched by the “new” Russia around the world, the grotesque Russian antiheroes from past century films seem almost like documentary portrayals of today’s Russians. They enjoyed looking “bad” in the eyes of the world so much that they played along and turned into real monsters.

For many years, films featuring “bad Russians” were perceived as a typical Hollywood cliché, a relic of the Cold War. Brutal cruelty, cunning, cynicism, crude manners, and fanatical, almost religious obsession with communist ideas, along with the traditional Kalashnikov and vodka bottle – this was how Russian (and until the early ’90s, Soviet) antiheroes were depicted by Western filmmakers. Yes, these were traditional genre clichés with a set of unchanging attributes – just as a vampire is impossible without fangs and a coffin with soil, or a werewolf without a full moon and silver bullets, Russian villains in Western cinema were always shadowed by the formidable KGB, FSB, or Russian mafia. And somehow, looking at these cinematic Russian villains, viewers overlooked a simple point – at the core of any stereotype lies a pattern, which is why this stereotype was formed. The pattern and experience of those who encountered the real-life prototypes of “caricatured bad Russians” and survived.

The partial softening of the image of Soviet citizens and intelligence officers, the “ideological enemies” from the socialist camp, began to emerge gradually during the so-called “detente” period. This era, associated with Leonid Brezhnev’s rule in the USSR and the presidencies of Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan in the USA, reached its peak with Mikhail Gorbachev’s rise to power, his “perestroika,” and attempts at democratizing the Soviet Union. During this time, films like “Moscow on the Hudson,” where a Moscow circus saxophonist (Robin Williams) defects while on tour in America, appeared in the West. Or the previously mentioned action film “Red Heat,” in which Soviet Captain Ivan Danko (Arnold Schwarzenegger) travels to Chicago to catch Georgian drug lord Viktor Rostavili with an American partner (James Belushi).

Sting’s song “Russians” from his 1985 album “The Dream of the Blue Turtles” also spoke of seeking understanding and the belief that “There’s no such thing as a winnable war / It’s a lie we don’t believe anymore.” Sting even used a fragment of a suite by Russian composer Prokofiev for the melody – the desire to find common ground and live in peace and harmony was reflected in the Western pop culture enchanted by “perestroika” and “glasnost”:

“Believe me when I say to you

I hope the Russians love their children too…”

In the late ’80s, this sentiment instilled hope. Today, against the backdrop of half a million irrecoverable Russian losses in the war with Ukraine, bombings of Ukrainian maternity hospitals, children’s hospitals, and residential areas by Russian missiles, the phrase “the Russians love their children too” seems at least debatable.

In reality, Russia – tsarist, socialist, and today’s FSB-ruled criminal clan – has always been ruthless to its own and others’ children. Daily proof of this can be found by simply opening the news feed under the hashtag #RussianUkrainianWar – every day, Russian leadership drives its citizens into bloody assaults to level another Ukrainian village or city. Why? Because they can.

From the late ’90s to the mid-2010s, Russians ceded the title of the world’s top terrorists to Arabs, Balkan militants, and Latin American dictators, moving into the category of internal threats – films about the Russian mafia became a regular feature in global cinema. Boris ‘The Blade’ from Guy Ritchie’s “Snatch,” Nikolai Luzhin from David Cronenberg’s “Eastern Promises,” or the caricatured Russian mafia clan from the first “John Wick” by Chad Stahelski – these were Western culture’s reflections on Russian integration into the global community.

However, the spy games that lifelong Russian dictator Vladimir Putin began playing from the start of his first term were also reflected in cinema. Otherwise, where would FSB killer Kirill (Karl Urban) from “The Bourne Supremacy” or international terrorist Egor Korshunov (Gary Oldman) from “Air Force One” come from? One of the most “ambiguous” and controversial images of a Russian intelligence officer was GRU officer Yevgeny Gromov (Costa Ronin), a character in the final seasons of the series “Homeland,” which focused on US-Russia spy games. Seasons 7 and 8 of “Homeland” were released after Russia’s hybrid invasion of Ukraine, and the devilish cunning, deceit, and cynicism of Russian spies resurfaced as dominant traits.

In 2020, Christopher Nolan’s sci-fi action film “Tenet” featured Russian oligarch and arms dealer Andrei Sator (Kenneth Branagh) as the main antagonist in an unprecedented temporal war between the past and the future. This demonic character, upon learning of his terminal illness, decided to take the entire world to the grave with him, betraying his contemporaries and serving future people in their war for resources. Doesn’t this remind you of Putin, who now openly considers himself the embodiment of the state and, in the event of a possible defeat in the war, is ready to destroy the entire world?

In 2022, the British produced the miniseries “Litvinenko” starring David Tennant, which told the story of the polonium poisoning of former Russian agent Alexander Litvinenko – here, direct accusations in international terrorism were made against Russian intelligence services and the dictator Putin behind them.

Surprisingly, the closest to capturing the real image of modern Russian soldiers were brothers Matt and Ross Duffer, showrunners of the teenage fantasy series “Stranger Things.” By collecting and reinterpreting all the clichés of the era (the series is set in the 1980s, against the backdrop of the US-Soviet confrontation), the Duffers in the fourth season showed the true face of Soviet (Russian) soldiers in a storyline dedicated to rescuing one of the characters from a Soviet prison camp in Kamchatka. The mystical monsters from the parallel world seem like cute animals compared to the brutal cruelty and roughness of KGB agents and camp guards.

To see that their depictions are not exaggerated or grotesque, one only needs to watch numerous videos of Russians fighting in Ukraine, documenting their war crimes and genocidal policies against Ukrainians on social media.

This comparison makes it clear that over the three decades since the collapse of the USSR, the bearers of the world’s main existential threat have not changed, remaining the same semi-wild, thoughtless cogs in the totalitarian system as they were during the Cold War era.

Source: The Gaze