As digital technologies become more advanced, we increasingly find ourselves going to the cinema not to see the real faces of our favorite actors but rather their digitally altered counterparts. Sometimes it’s justified and well-executed, but not always.

In the retro film “Vivre Sa Vie” by Jean-Luc Godard, there is a particularly poignant scene in the history of cinema. The heroine Nana (Anna Karina) watches the classic silent film “The Passion of Joan of Arc.” On the screen, there is a close-up of Joan’s face, who, upon hearing her verdict, sheds a tear. Then, there is a close-up of Nana’s face, who is so moved that she too sheds a tear. The audience, in turn, cannot tear their eyes away from Nana’s emotionally charged face and is compelled to reach for a handkerchief to wipe their own wet eyes. The scene unfolds in silence, without special effects, and even the film itself is not in color but black and white. The magic of cinema is created solely by the expressive faces of two great actresses:

This is how iconic films were made 60 years ago. However, in recent years, directors have shown an increasingly unclear desire to do something extra with the faces of their actors—whether to rejuvenate, age, or even replace them with others entirely.

The Digital Elixir of Youth

In nearly every other film, there’s some form of flashback or flash-forward. If it’s within a plus or minus range of 5-10 years, changing the age appearance of actors can be easily managed with makeup. But what about when the leap in time is 20, 30, or even 50 years into the past, and specifically into youth? Regular makeup can transform an actor who’s a teenager into a senior citizen convincingly, but the reverse, turning an older actor into a young character, is a different challenge altogether.

There are essentially two options: the classic approach, which involves hiring a younger actor who resembles the older one, or following the trend of using digital technology to de-age the existing actor.

Photo: Brad Pitt as Benjamin Button in digital makeup, Source: Collage by Leonid Lukashenko

When this trend first emerged, it was intriguing. Recall how in 2008, a 45-year-old Brad Pitt gradually became younger in the film “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” until many believed he looked even more handsome than in his actual youth. What mattered most was that the essence of the story, about a person born old and gradually growing younger, required one actor throughout the entire film. This was justified, and director David Fincher managed to strike a balance between makeup and unobtrusive digital technology.

However, the same cannot be said for the third installment of “X-Men” (2006), where Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen (both over 60) underwent “digital skin transplantation” for a flashback that aged them backward by 20 years, but ended up making them look like smooth reptiles. Their appearance triggered something akin to the “uncanny valley” effect (a hypothesis in robotics suggesting that human-like objects provoke feelings of eeriness when they appear almost but not exactly like real humans).

Computer graphics technology has evolved, but even after a decade, it still fell short of perfection. In 2016, in “Captain America: Civil War,” Robert Downey Jr. underwent a transformation that probably justified his choice of adding “Junior” to his surname. The special effects wizards had to process 4000 frames from late 80s films where the actor was still young. Young Tony Stark moved dynamically on screen (which is always more challenging to fake than static acting) and even had microscopic skin imperfections. However, the overall impression was that of a highly detailed and realistic bio-robot rather than a living person.

A year later, in another “Pirates of the Caribbean” installment, they tried to rejuvenate Johnny Depp and ended up with skin that looked too flawless, resembling a young model rather than a person who had aged naturally.

In 2019, everyone anticipated a wow-effect from the action-thriller “Gemini Man,” where Will Smith’s character tries to kill his 30-year-younger self. They spent twice as much on special effects as Smith’s salary. They even shot the entire film at 120 frames per second instead of the standard 24. However, it didn’t save the film, which bombed at the box office and cost Paramount Studios millions in losses.

Photo: Young and old Will Smith in “Gemini Man”, Source: Collage by Leonid Lukashenko

The same year, Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman” attempted to rejuvenate 76-year-old Robert De Niro once more. On one hand, the actor was filmed simultaneously by three cameras (two of them being infrared) to create a 3D model that could be edited in post-production to remove wrinkles and tighten the skin. De Niro’s face did indeed undergo a high-quality transformation. However, on the other hand, his physical movements still reflected those of an elderly person. A similar strange dissonance was experienced with 80-year-old Harrison Ford, who was digitally de-aged by half for the latest “Indiana Jones” movie. Regardless of how you look at it, the digital elixir of youth has yet to work its magic in the world of cinema. Those who cherish nostalgia may find it more satisfying to revisit old films featuring De Niro and Ford, where they remain forever young.

Indeed, it’s bittersweet when beloved actors age, but it’s even more disheartening when they attempt to turn back the irreversible passage of time, often sacrificing the authenticity of their performances. However, there’s no absolute need for this. Clint Eastwood, in his 90s, still portrays 90-year-old characters with unparalleled charisma, outshining many younger actors. Likewise, Tom Hanks, who played a senior citizen in “A Man Called Otto” last year, utilized his younger son, Truman Hanks, in flashbacks to portray the character’s early adulthood. This approach offers something more intriguing – an opportunity to observe how the world’s favorite “Forrest Gump” has aged, how similar his son is to him, and whether the younger Hanks is as talented an actor as his father.

Digital Resurrection

The use of digital manipulation on an actor’s face appears more justified when the actor has already passed away, yet there’s a need for their presence in a film. For example, in 2000, actor Oliver Reed, who played Proximo in “Gladiator,” tragically passed away before filming two crucial scenes. Reed, known for his struggles with alcohol, had consumed a significant amount of alcohol in a bar between takes, resulting in his untimely death from a heart attack. The bar was later renamed “Ollie’s Last Pub,” and the director faced a dilemma of either reshooting all the completed scenes with Reed or coming up with an alternative solution for those unfinished scenes. Creating a believable substitute proved to be a simpler and more cost-effective option. As a result, the two scenes were reshot with a look-alike actor, and Reed’s face was digitally added in post-production.

Was this justified? Yes. Just as it was justified in the case of Paul Walker’s digital resurrection in the seventh “Fast & Furious” installment. The actor tragically died in a car accident before completing all of his planned scenes. Walker’s cousin doubled for him, and his face was digitally imposed onto the double in post-production to complete the film.

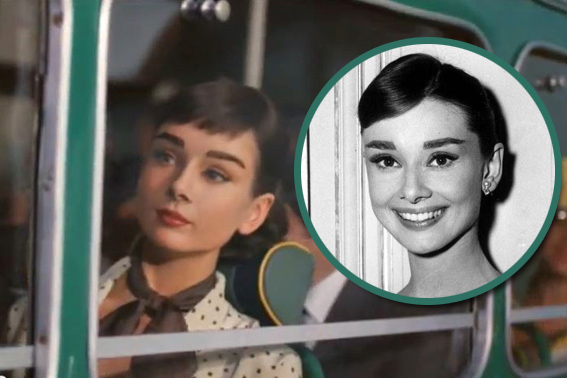

However, is it justified when digitally resurrecting a deceased actor becomes a goal in itself rather than a solution to a pressing issue? Consider the Galaxy chocolate advertisement featuring Audrey Hepburn, who had passed away more than 20 years earlier (and was depicted in her younger self from the 1953 film “Roman Holiday”). To achieve this, two stand-ins were used: one resembled Hepburn’s body, and the other her face. Through post-production editing, they seamlessly combined the two performances and enhanced the facial likeness through computer graphics. The realism of the special effects, as of 2014, was astonishing. Yet, the ethical implications of such a resurrection were unclear. Should we continue exploiting the beauty and iconic status of classic characters, even after the actors who portrayed them have long passed? Or is it more meaningful to embrace generational shifts and new idols rather than perpetually exploiting the same beloved but canonical cinematic personas?

Photo: Digital and original Audrey Hepburn, Source: Collage by Leonid Lukashenko

The creators of “Star Wars” have also shown a fascination with digitally resurrecting deceased actors. In the movie “Rogue One” (2016), both Peter Cushing, who portrayed Governor Tarkin in the original 1977 “Star Wars,” and Carrie Fisher, who played Princess Leia, were digitally brought back to life. On set, other actors portrayed them, and their performances were later modified in post-production to resemble the originals more closely.

This approach can be somewhat schizophrenic. You go to the cinema in 2016 and watch the same franchise you watched in the late ’70s, and what’s more, the actors look the same, as if those 30-40 years never happened. It brings to mind the film “A Beautiful Mind,” where Russell Crowe plays a schizophrenic mathematician who interacts with imaginary people but only realizes it many years later when they haven’t aged. After all, hallucinations, unlike real people, don’t grow old. What can be said then about modern cinema and its viewers who have grown fond of timeless iconic characters that are not allowed to age or die? Do these films, with their use of digital facsimiles instead of real people, make us all a bit schizophrenic?

Dealing with Outcasts and Unwanted Faces

What happens when a film or TV series is entirely shot, and later on, one of the actors becomes persona non grata? Not just unwanted, but to the extent that studios are left with two choices: either archive the entire filmed material or replace the outcast’s face (and voice) with someone more favorably regarded? Not long ago, the latter option was nearly impossible. However, since the 2017 epidemic of pornographic deepfakes, this groundbreaking technology has found its way into the realm of cinema.

The essence of this technology lies in the antagonistic interplay between two neural networks. The first network strives to create highly realistic fakes, while the second aims to detect and reject them by comparing them to genuine images. This is the realization of unsupervised machine learning algorithms, and it’s making the process of automatically generating deepfakes more efficient, faster, and significantly cheaper.

For instance, when Kevin Spacey faced accusations of sexual harassment in 2017, Ridley Scott found himself in a quandary. Twenty-two scenes featuring the disgraced actor had already been filmed for “All the Money in the World.” Releasing the film as-is would have led to box office failure and vehement protests from activists. Therefore, Scott re-shot the scenes with Christopher Plummer, replacing Spacey, at a cost of $10 million. If he had used deepfake technology, he could have saved almost all of that money. Even better would have been to wait a little longer, as this summer, Kevin Spacey was acquitted of all charges.

Deepfakes also proved useful after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Russian actors had occasionally appeared in Ukrainian TV series before. Some of them had already been filmed and were ready for broadcast as of February 24, 2022. However, airing shows featuring citizens of the occupying country would have been suicidal for any Ukrainian channel. For example, last spring, in one such series called “The Last Letter from a Loved One,” the face of a Russian actor was replaced with a Ukrainian one. Nevertheless, the show never made it to air because, immediately after its announcement, civil society expressed outrage, prompting the show’s producer, STB channel, to issue an apology and cancel its broadcast. In Russia as well, actors who expressed anti-Putin sentiments after shooting concluded had their faces swapped with those who were loyal and spineless, or conversely, ideologically aligned with the Kremlin.

The Future in a Fake Style

Technical progress is challenging to halt. Modern deepfakes offer savings in both money and time in film production while opening up unprecedented creative possibilities. Some actors are embracing this trend, envisioning a future where they can sell digital copies of their image to studios and enjoy vacations without the grind of working long hours, enduring the whims of tyrannical directors, and more.

However, the first episode of the sixth season of “Black Mirror,” in its signature genre of dark satire, hints at a bleak outcome. In it, Salma Hayek sells her image to the studio, which can now exploit it perpetually in various stories and scenarios without her consent. Once Hayek realizes this, it’s too late to rectify. Consequently, some contemporary stars are considering inserting clauses into their contracts with studios that define the limits of acceptable and unacceptable use of their likeness, even after their physical demise.

Keanu Reeves is among those opposing deepfakes. In an interview with Wired, he ponders,

“When you act in a film, you know that the footage will be edited, but you are involved, and your perspective is taken into account. When you enter the world of deepfakes, your viewpoint is absent…”

Furthermore, in the future, actors risk becoming obsolete as they could be completely replaced by digitally generated creations that may even outperform them.

Photo: Keanu Reeves in “Martix Resurrections”, Source: Warner Bros

Yet, this scenario is likely not imminent. What’s on the horizon, however, is Robert Zemeckis’s new film titled “Here.” It promises to be a deepfake sensation in the world of cinema, as it employs technology developed by Metaphysic, known as the “Mirror of Youth.” Its primary distinction from its counterparts is that the deepfake is generated in real-time, overlaying an actor’s image as they perform before the camera. Post-production becomes unnecessary. In this film, Tom Hanks and Robin Wright will be digitally rejuvenated using this method. The premiere of “Here” is scheduled for 2024, and anticipation is building.

Who knows where the deepfake revolution in cinema will lead us? We still empathize with the characters on screen when watching Godard’s “Vivre Sa Vie” 60 years after its premiere. Sixty years from now, will future generations still feel the same connection to artificial deepfakes, which are currently being mass-produced with enthusiasm? It’s a significant question that remains unanswered.

Source: The Gaze