The two largest developing economies are no longer developing as rapidly. A slowdown in China and India could have far-reaching effects on the world, creating echoes that will be felt even where they are least expected. Interestingly, this crisis is not yet truly global. Recent protective measures implemented by developed countries against aggressive exports appear to be providing them with real relief. These measures could act as firebreaks, separating more stable economies from those already in turmoil. If you want to monitor the intensity of this economic fire, keep an eye on global prices for oil, iron ore, copper, and lithium.

In reality, industrial production in India and China is slowing down quite quickly. This is a serious concern for two countries with populations of 1.42 billion and 1.41 billion, respectively, and GDPs of $3.6 trillion and $17.9 trillion. Together, these two countries account for 35.38% of the world’s population and 20.48% of global GDP. And now, there is a rapid deceleration occurring.

Pessimism is Raging

Manufacturing in China fell to its lowest level in six months in August, according to a survey conducted on 30 August. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) from China’s National Bureau of Statistics fell from 49.4 in July to 49.1 in August. It’s important to note two details: this is the sixth consecutive month of declining sentiment, indicating a consistent downward trend over the past half of year. Additionally, this is the fourth consecutive month that the index has been below 50, signalling a negative trend in production. Moreover, the August figure is significantly worse than the average forecast of 49.5 obtained from a Reuters poll.

India’s Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is also declining. The index fell to a three-month low in August, according to the HSBC India Manufacturing Managers Purchasing Index released by S&P Global on 2 September. The PMI in India decreased from 58.1 in July to just 57.5 in August. However, conditions in India currently appear much better than in China: first, the PMI in India is still above 50, which indicates overall positive sentiment, and second, this index is above the long-term average of 54.

Indeed, India’s relative advantage is also reflected in the IMF’s forecasts for these two countries: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects China’s GDP to grow by 5% in 2024, while India’s is projected to increase by 7%. For the following year, the IMF anticipates growth of 4.5% for China and 6.5% for India. This trend is understandable, as India’s GDP per capita is still about five times lower than China’s. China once grew at a pace similar to India’s current rate, but those days are over.

The slowdown in China’s growth is not only due to an increase in GDP per capita; as an economy grows larger, it becomes more challenging to maintain high growth rates. China is currently experiencing a crisis driven by ignoring economic realities in favour of directive economic management. It is not that India is a particularly free liberal market, but in terms of the power of autocratic institutions, Beijing has certainly gone much further than New Delhi.

The problem with the Chinese and Indian economies lies in their pursuit of GDP growth at any cost and significant militarisation.

Regarding militarisation, this is no joke: India spends 2.32% of its GDP on the military budget, while China spends 2.68%. Compare this to the 2% target that most European countries still consider an unattainable goal for defence funding.

Photo: China remains the world’s largest importer of iron ore, but its appetite is being forcibly reduced due to the crisis in construction and engineering.

China First, India Next

China’s excessive export promotion and state subsidies have not only spoiled Chinese exporters but also led developed countries to shield themselves from Chinese goods with very high tariffs. Extremely high tariffs against Chinese electric vehicles, steel, and aluminium are being imposed one after another. In just the past few months, additional tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, steel, and aluminium have been introduced in the US and Canada. The US tariffs are particularly high, set at 100% of the price. Meanwhile, in the EU, protective tariffs of several tens of percent have been implemented against Chinese electric vehicles, varying from manufacturer to manufacturer.

Such strong measures have not yet been applied against India, but it may only be a matter of time. China is facing a strong backlash in its trade expansion not only because of the influx of Chinese goods but also due to Beijing’s close support for Moscow’s aggressive war in Ukraine. Firstly, China purchases Russian oil, gas, and various raw materials. Secondly, through Chinese firms, sensitive goods and technologies flow to the Russian military-industrial complex, as reported multiple times by The Gaze. Both of these actions fuel Russia’s war in Ukraine.

India, due to the significantly smaller size of its economy, consumes far less Russian oil and various raw materials. However, the visibly close ties between New Delhi and Moscow are seriously irritating developed countries. This could eventually lead to the introduction of strong protective measures against Indian goods. Moreover, against this backdrop, the populist policies of the current government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, have started to flourish. After not particularly successful national elections, Modi is trying to please voters ahead of this year’s local elections. Naturally, this threatens healthy economic growth and lays the groundwork for future problems.

The slowdown in China and India is a double-edged process. The loss of Western investment and damage to supply chains are not what is desired in Washington, Brussels, Tokyo, Paris, Seoul, and Berlin. They would prefer to see a soft landing for the Chinese and Indian economies under total control. They would also like this soft landing to be accompanied by the relocation of supply chains from India and China to other countries—Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand, and even Ukraine, not to mention Central European countries. Additionally, developed countries would prefer to see a more cautious foreign policy from China and India. This is because everyone has been deeply shaken by Russia’s example—how petrodollars earned can be used to destabilise the world and wage aggressive war.

However, this process of a soft landing is sometimes getting out of control, at least in China. There, a sharp deterioration is occurring not only in export-oriented production but also in construction, which consumes a lot of structural steel and thus requires large volumes of imported iron ore. Economic slowdown naturally limits appetite for oil. Restrictions on the import of Chinese electronics and electric vehicles significantly reduce demand for materials such as copper, aluminium and lithium.

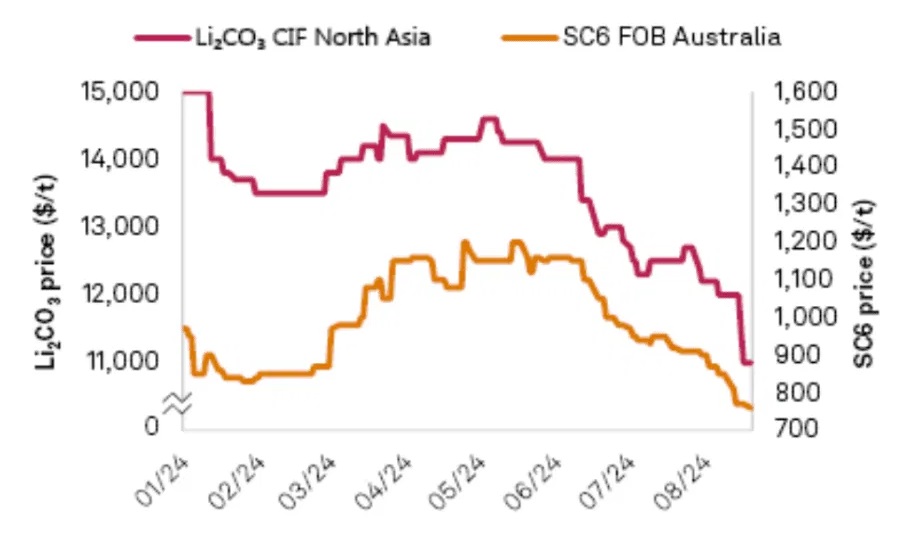

Photo: Tariffs on the import of electric vehicles into the US and the EU are putting pressure on lithium prices. Source: S&P Global

Monitoring Prices

Prices of key materials can serve as an indicator of the pace of this soft landing. In early September, oil prices rose slightly, reaching $77 per barrel for Brent crude futures. However, oil has still decreased by about 10% since early April 2024, when it peaked for the year.

Iron ore prices on the global market have dropped by 31.3% from January to early September this year. This significant decline has pushed many iron ore companies into low-profit zones and laid the groundwork for a potential future shortage of raw materials, as investments in new deposits are reduced. This is primarily a result of the crisis in China’s construction sector.

Falling prices for raw materials and oil are very beneficial for developed economies and contribute to greater geopolitical stability.

Copper prices have decreased by 17.6% from their peak in mid-May to early September, even after rebounding from their early August low. Comparing May to early August, there was a decline of 22.7%. Copper is a key material for manufacturing electric motors and both alternative and traditional sources of electricity. Therefore, the first signs of an economic crisis are almost immediately reflected in copper prices.

Lithium, a key raw material for modern batteries, has seen an even sharper decline. Lithium concentrate supplied by Australian mining companies fell by 33.9% from its peak this year in May to the end of August. The raw materials supplied by Chinese mining companies decreased slightly less over the same period, by 24.1%. A clear trend is evident here—immediately following negative news about tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles in the EU and the US, the prices of key raw materials began to tumble.

Interestingly, the fall in raw material and oil prices is highly beneficial for developed economies and contributes to greater geopolitical stability. Lower prices for raw materials and oil help curb inflation, which central banks in the US, the UK, the EU, and Japan are actively fighting. Furthermore, falling raw material prices have a sobering effect on the leaders of autocratic regimes who rely on petrodollars and the sale of other raw materials.

Source: The Gaze