It appears that gloomy forecasts about the Chinese economy facing tough times are coming true. While just a few months ago there were hopes that China could overcome economic challenges without bloodshed, the scale of problems in a country that demonstrated an example of rapid, even aggressive growth is becoming evident. How did such massive problems arise in a nation that showcased wild economic growth? Why are these issues escalating so rapidly? Most likely because the government overly used financial levers to inflate GDP, pump up the real estate market bubble, and expand export expansion. These are mistakes already experienced by developed countries, and the temptation to repeat them is too great. Of course, Chinese economic troubles affect the state of the global economy overall. However, in some instances, they have a somewhat positive effect through the potential lowering of commodity prices, for example.

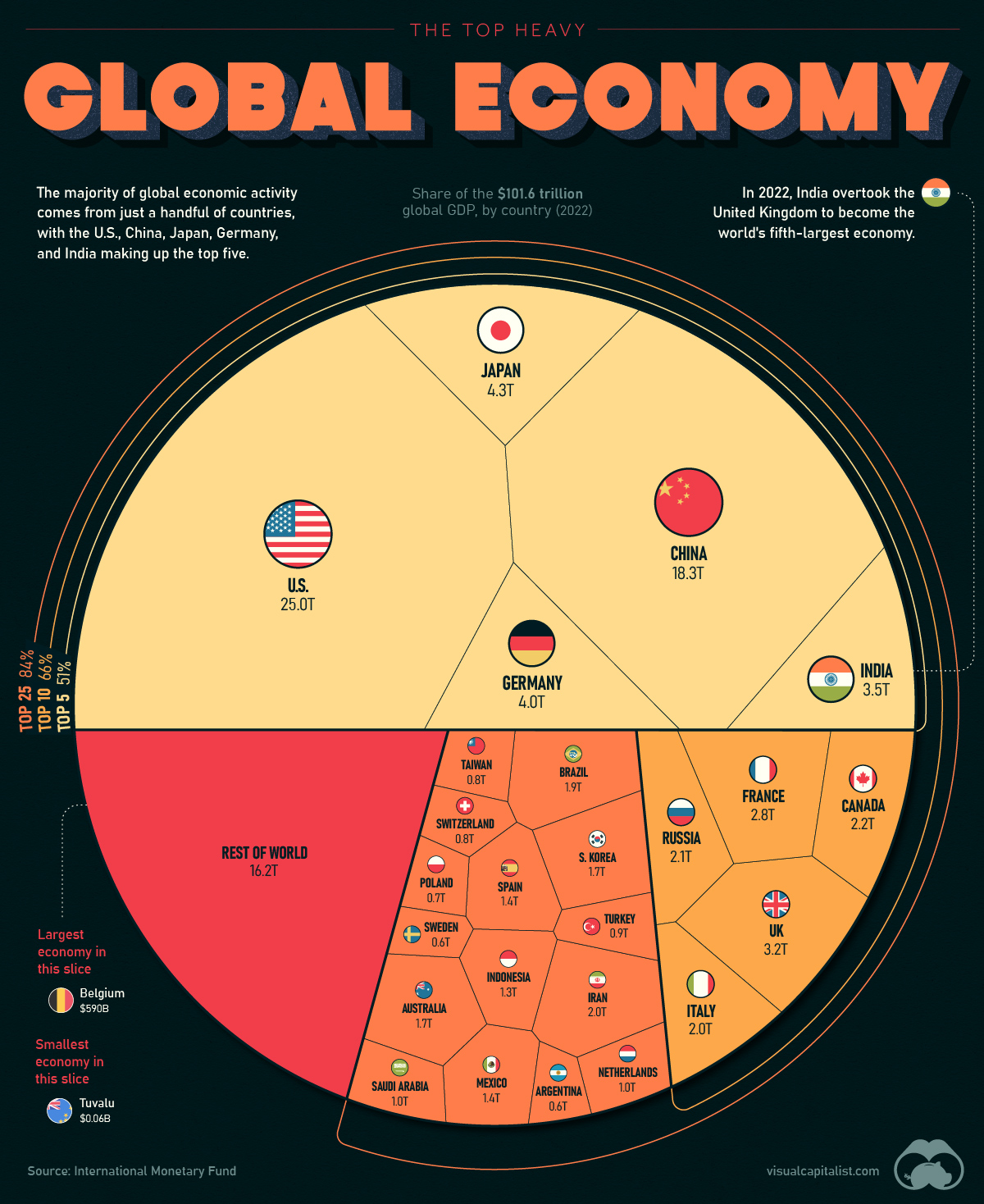

Photo: China ranks among the top five largest economies globally, accounting for approximately 18% of the world economy. Source: IMF, Visual Capitalist

In early December, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a substantial article with a striking headline, “China Stumbles but Has a Chance to Avoid Economic Collapse.” The author, Eswar Prasad, a senior professor of trade policy at Cornell University’s Atkinson School of Management, detailed the reasons for the crisis facing China.

China’s GDP growth is slowing, price dynamics are in the negative zone, exports are contracting, and the banking system is teetering on the edge. All of this does not bode well for China. Beijing is reaping the fruits of years of state intervention in the economy and pumping the real estate market with cheap loans. Not only the real estate market but all those grand infrastructure projects – they may sharply boost GDP, but they are hardly beneficial to the economy’s health.

“But this does not mean that a financial or economic collapse is inevitable. If the Chinese government plays its cards right, a more favourable future for the Chinese economy with moderate but sustained economic growth can be envisioned,” believes Eswar Prasad.

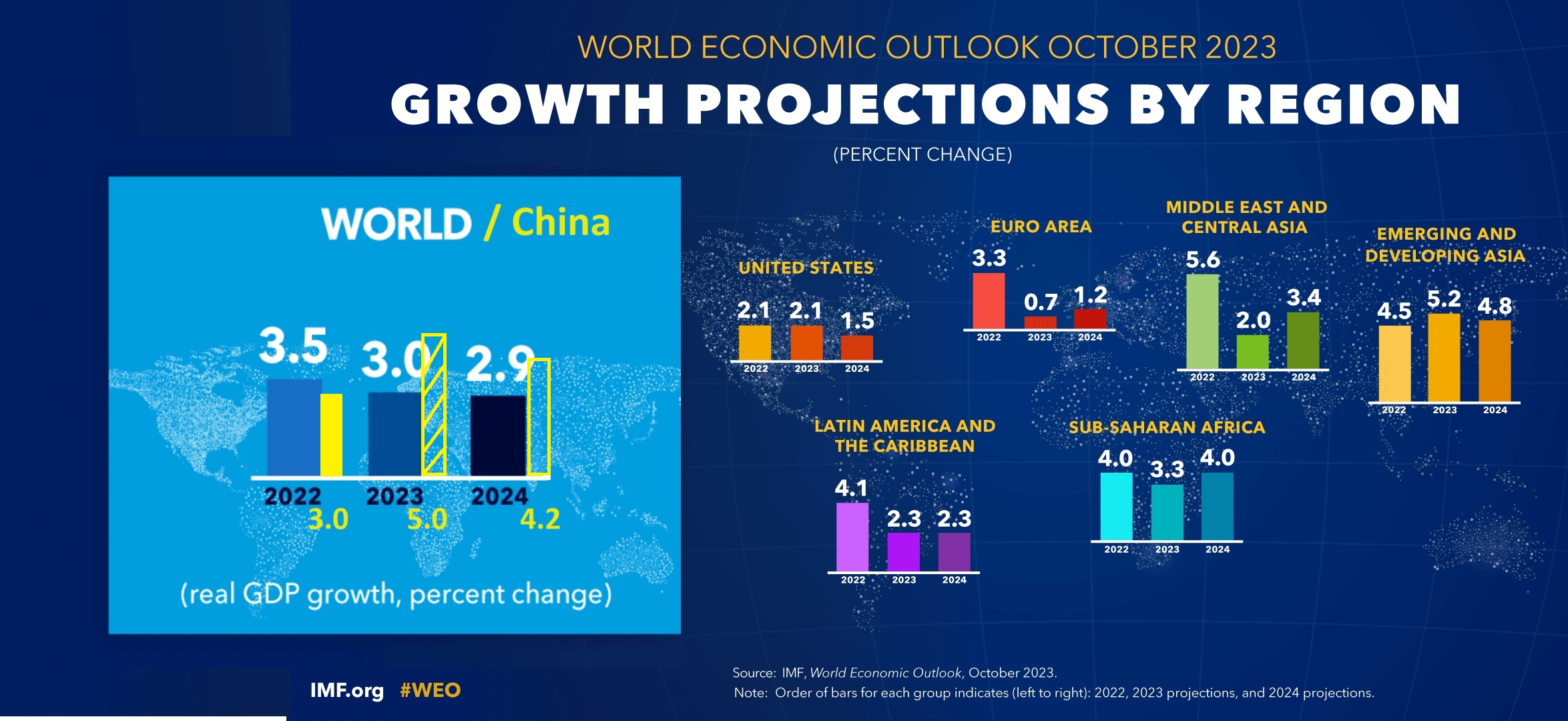

Photo: How China’s economy is growing against the backdrop of the global and various regional economies. Source: WEO IMF

GDP Growth on the Edge

In the third quarter, China’s economy slowed to 4.9% after growing by 6.3% in the second quarter. For 2023, the IMF forecasts a GDP growth of only 5% for China. The forecast for 2024 is even more pessimistic: China’s GDP is expected to grow by 4.2%.

On the one hand, many countries could only dream of such results, even the US and the EU, where the economy grows by 1-2% per year. But what might be a blessing for some is almost a catastrophe for China. And it’s a political catastrophe too, as for the country’s leadership, anything less than 6% annual growth is considered a failure.

If we track China’s GDP growth over the last 20 years, economic growth has never been less than 6%, and in some years, it reached 14%. The only exceptions were 2020, when the whole world was hit by COVID-19, and 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. Additionally, each year, the Chinese government sets a target for GDP growth, averaging 5-5.5%. So, if China’s economic growth is below this target range, it’s a clear sign of a crisis.

The situation with consumer demand is also causing concern. For two consecutive months, in September and October, China recorded consumer deflation. Producer prices have been decreasing for 13 consecutive months. According to economist Den Van from Hang Seng Bank, these inflation indicators reflect “a decline in purchasing power and weak consumer confidence.” Considering that households form the backbone of China’s economic growth, this is a bad signal.

External trade is not comforting either. China’s exports are shrinking (-6.4% in October), while imports are growing (+3% in October). This indicates significant problems with competitiveness among local manufacturers.

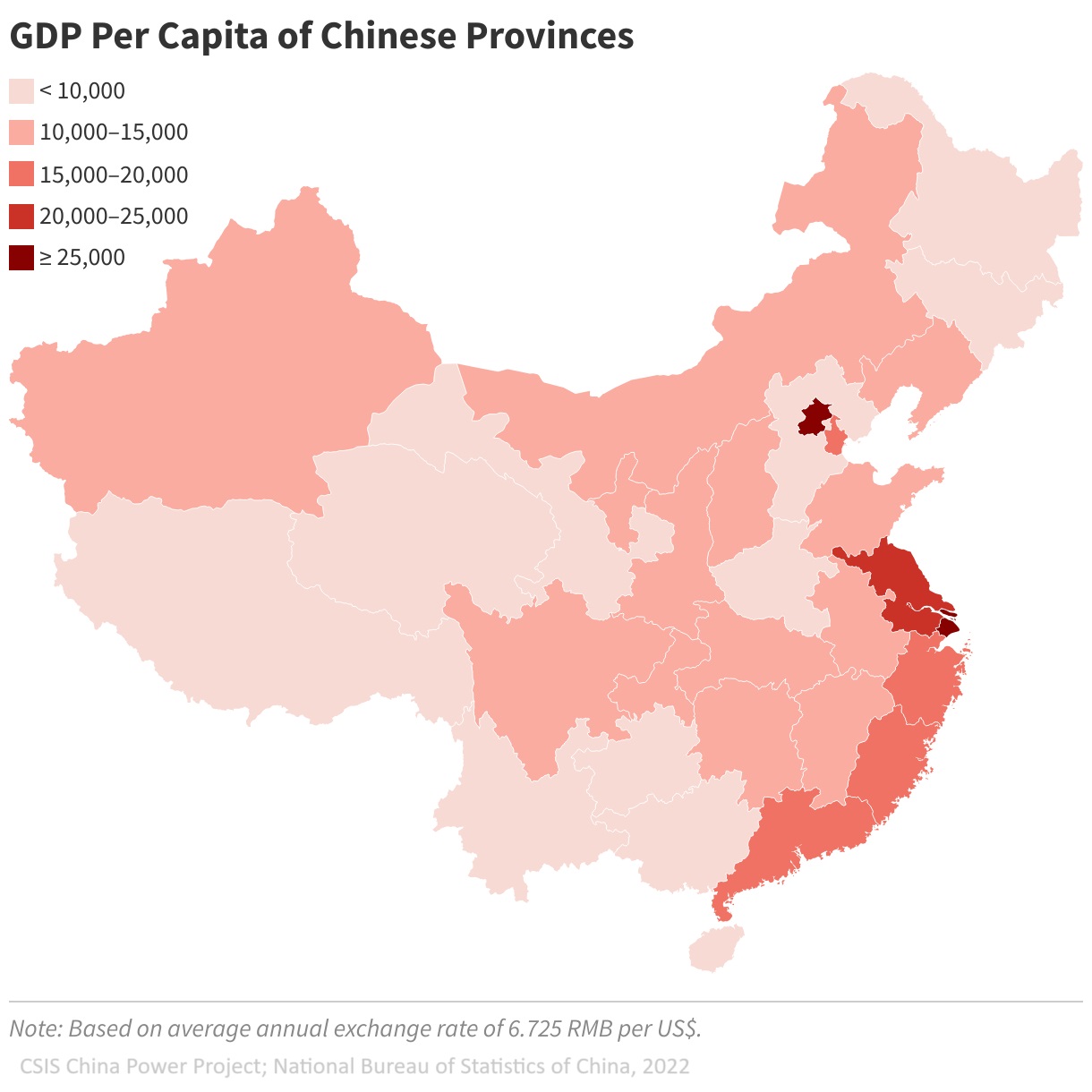

Photo: Where the wealthiest Chinese reside: GDP per capita of Chinese provinces. It’s evident how economic life is concentrated in coastal regions and near the capital. Source: CSIS China Power Project; National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2022

New Mortgage Bubble Emerging

Beijing’s major headache lies in the real estate sector, tightly linked with banks and literally oozing credit funds. In August, Evergrande Group, one of the largest property developers, declared insolvency and an inability to settle debts with creditors. In November, a similar fate befell the investment bank Zhongzhi Enterprise, primarily investing in real estate. Its leadership warned investors that the company wouldn’t be able to repay debts as “the volume of assets available for debt repayment is significantly lower than the total amount of obligations.”

For many years, real estate investments played a pivotal role in fuelling the Chinese economy, covering a substantial portion of state expenses. Local authorities, for instance, sold land to developers, filling the coffers with money.

Real estate and related industries contribute to about 30% of China’s GDP. However, as experts from Nikkei point out, capital investments in new developer projects are diminishing as the demand for real estate has reached saturation.

Therefore, if systemic difficulties arise in the real estate sector, it will not only weaken the banking sector but also impact state finances and, inevitably, exacerbate unemployment.

Domino Effect

China’s problems extend far beyond its borders. This is partly because Beijing is a major consumer of raw materials, oil, gas, iron ore. A slowdown in China’s economic growth will lead to a reduced demand for resources, resulting in falling prices and losses for other commodity-exporting countries. However, it will significantly improve the situation for industrially developed countries, which have been suffering from the previous overheating of commodity markets.

Anticipating events, OPEC+, for example, has already decided to cut oil production by a million barrels per day. Although it’s uncertain whether this will help maintain prices. China has accumulated significant oil reserves, posing a risk that it will reduce oil purchases in 2024. This would be painful for the industry as Beijing consumes about 13% of the world’s total oil.

The import of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to China is currently increasing. In the first 9 months, Beijing increased LNG purchases by 10.1% year on year. However, this is still insufficient, considering that LNG supplies to China decreased by 20% in 2022. Given that Beijing’s energy security relies on coal (China mines 50% of the world’s anthracite), the recovery of LNG demand remains under threat.

The situation in metallurgy is also ambiguous. On one hand, China is boosting iron ore imports. From January to October, the import of this raw material increased by 6.5% year on year. At the same time, metallurgical companies in China are reducing production. A decline in production volumes in this sector has been observed from July to October. One reason is the reduced demand for metal, a key crisis indicator, especially in construction.

Photo: Fast, slow, slower: the growth rates of China’s real gross domestic product (GDP) from 2012 to 2022 with forecasts until 2028. Source: The Gaze, Statista

Time to Seek Compromises

China’s economy is directly affected by Beijing’s pursuit of superpower status, yet it lacks complete economic self-sufficiency for this goal.

China maintains a loyal position to Russia regarding the war in Ukraine, even assists the Russian military-industrial complex. This leads to disparities in political matters and trade cooperation with key partners such as the USA and the EU, Japan as well.

However, a slight glimmer of hope emerged for a thaw between Beijing and Washington after the meeting between US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping on November 15. It didn’t yield tangible results, and it wasn’t expected to, as the primary message was the initiation of dialogue between the US and China. This is logical, given that both countries need each other: the US is the largest importer of Chinese products, while China maintains its claims on Taiwan, a crucial source of semiconductors and other microelectronics worldwide.

The crisis is unlikely to escalate into direct confrontation. At least Biden pledged not to alter the “One China” policy. However, predicting the logic of the Bejings authoritarian regime remains challenging.

Relations between China and the EU also do not inspire optimism. It resembles a cold war scenario: the EU is steadfast in its intentions to reduce dependence on the supply of rare earth elements from China.

While the EU acknowledges that China entirely supplies Europe with elements essential for automotive manufacturing, alternative energy, and instrumentation, Brussels sees no need to reconcile with this further. Beijing has been using the export of such raw materials as a lever for political influence. Or, more precisely, as a geopolitical leverage.

In November, the EU Council and the European Parliament reached a preliminary agreement on a crucial raw material law, one of its provisions involving the diversification of the supply of such raw materials. The EU envisions importing from Turkey, Africa, and Latin America as an alternative. Additionally, Europe aims to self-supply 35% of rare earth elements through domestic extraction and recycling. Understandably, the transition will take years. However, losing such a colossal market as the EU could be irreparable for China, further slowing down its economic growth.

In other words, Beijing faces a dilemma: whether to save the economy and choose a pragmatic course or to preserve its imperial image and pumped statistical figures.

Source: The Gaze